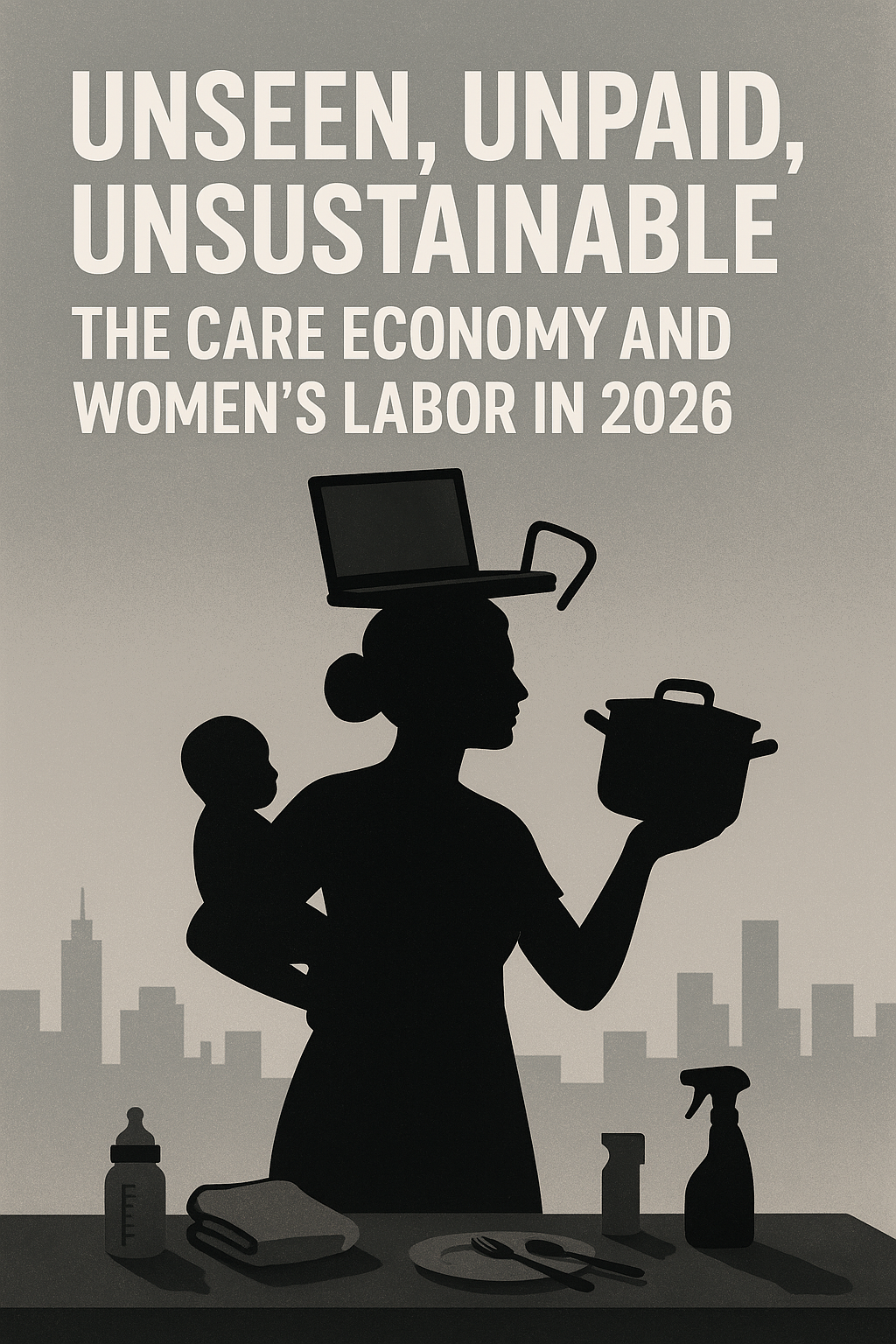

Some crises don’t announce themselves. They don’t arrive with sirens, breaking news alerts, or policy debates. They unfold quietly inside homes between early morning alarms, school lunchboxes, medical appointments, late-night emails, and the soft, exhausted sighs of women who are holding up more than anyone realizes.

This is the caregiving economy of Bangladesh in 2026. And although it fuels everything around us, it remains invisible, unrecognized, and overwhelmingly carried by women. I have witnessed it my whole life. From my childhood, I saw my grandmother, my mother, my aunts all the super women whose strength was rarely acknowledged but always expected. These women begin their days before the sun rises, not because she is an early riser, but because she has no choice. By 6 a.m., she has prepared breakfast, ironed school uniforms, checked on her diabetic mother-in-law, packed tiffin for her children, and filled a water filter that never seems to keep up with demand. She hasn’t earned a single taka for any of it, yet the entire household would fall apart without her.

Women like my mother are everywhere in city flats, in rural joint families, in middle-class homes balancing rising costs, and in working-class households fighting inflation one day at a time. Their labor is unpaid, but it is the foundation on which Bangladesh’s formal economy stands.

Increasingly, more and more women belong to what researchers call the “sandwich generation.” In Bangladesh, this is painfully visible. A woman may be juggling her career at a bank or garment factory while also caring for a toddler and managing medical appointments for her aging parents. The pressure is relentless school admissions, hospital visits, rising food prices, household chores, and the emotional work of keeping everyone calm and cared for.

And then there is childcare, a luxury for some, an impossible cost for many. Daycare centers are still limited, and the good ones often consume nearly half of a woman’s salary. Many mothers in Bangladesh do silent math in their heads: If I spend most of my salary on childcare and transport, does it make sense to work at all? For countless women, the numbers simply don’t add up. Even when they stay employed, the penalties are real. A woman who takes maternity leave often returns to fewer responsibilities or subtle assumptions that she is “less serious” about her career. Mid-level promotions slow down. Supervisors hesitate. Some colleagues make comments that sting “Family comes first for you, na?” as if care is a weakness instead of a contribution.

The truth is, women’s unpaid labor is subsidizing the entire economy of Bangladesh. It subsidizes companies that don’t invest in childcare. It subsidizes families that rely on daughters and daughters-in-law to maintain harmony. It subsidizes cities that lack eldercare infrastructure. It subsidizes rural communities where women walk miles to collect water, cook, clean, and care for livestock, on top of caring for people.

And yet, we rarely pause to acknowledge this labor. Women’s time is treated like an endless resource – renewable, elastic, always available.

But it isn’t.

Behind closed doors, many women feel the strain. They don’t complain, because in Bangladesh, sacrifice is woven into the identity of motherhood, daughterhood, and being a “good bou (do as told daughter-in-law).” But the emotional cost is real. Dreams get postponed. Career ambitions shrink. Personal time disappears. Some days, women like Salma sit quietly after everyone sleeps, remembering the version of themselves they hoped to become before responsibilities swallowed their hours.

Bangladesh is changing fast digitally, economically, socially. More women are entering universities. More are joining the workforce. More are contributing to family income. But their unpaid caregiving responsibilities have not reduced at the same pace. Instead, they are carrying two full-time jobs: one paid, one not.

If Bangladesh truly wants to become a middle-income, inclusive nation by 2030 and beyond, it must confront this invisible burden. Affordable childcare, flexible work arrangements, eldercare support, women-friendly public transport, safe working conditions, and workplace policies that respect caregiving responsibilities these are not luxuries. They are essential to retaining women in the workforce and ensuring economic progress doesn’t rest on unpaid female labor.

Imagine a Bangladesh where women like Salma have help instead of pressure, choices instead of sacrifices, and recognition instead of silence. A Bangladesh where caregiving is shared within families, supported by communities, and acknowledged by institutions. A Bangladesh that understands that nurturing children, caring for elders, and managing households are not “women’s duties” they are national contributions.

The caregiving crisis in 2026 is not just a women’s issue. It is an economic issue. A social issue. A future-of-the-nation issue. And perhaps the most powerful step we can take right now is to tell these stories honestly stories that make the invisible visible. Stories that remind us that behind every strong economy is a woman who has been holding things together for far too long, with too little support.

Bangladesh owes these women more than gratitude. It owes them recognition, dignity, and structure. Their unpaid labor has carried the nation this far and it’s time the nation finally carried them back.

Leave a Reply